Blood supply is essential for life-saving surgeries, chronic illnesses, cancer treatment, and traumatic injuries. However, while artificial blood is being tested in the lab, some main components (such as platelets and plasma) cannot be manufactured. For this reason, blood donation, collection, and storage are crucial for patients in need.

The four main components of whole human blood are red blood cells (RBC), white blood cells (WBC), platelets, and plasma. Red blood cells contain hemoglobin, a transport molecule that allows them to pick up and drop off oxygen molecules around the body. White blood cells help protect the body from infection. Platelets are small cell fragments that form clots at wound sites to stop or prevent bleeding. Plasma (the largest component of our blood, making up about 55%) is the straw-colored liquid component of blood, working alongside water to carry salts, enzymes, cells, and other essential entities through the bloodstream. All these components together are flowing through our bloodstream in a form known as whole blood.

Blood’s relatively short shelf-life of 6 weeks conflicts with the fluctuating need for blood across the country. Plasma, which has the longest period of usability, can be frozen and stored for up to one year. Whole blood can last for 42 days when stored at just above freezing temperature, while lone samples of platelets can survive for a mere 5 days when stored in an agitating machine that keeps them in motion and suspended so they don’t clot.

One of the most memorable occurrences of wasted blood due to shelf-life was in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center. While less than 200 survivors required donated blood, 500,000 more units than average were donated in September and October of that year. As a result, more than 200,000 units of whole blood went unused and had to be discarded.

A potential solution to this problem is to dry the blood using a sugar-based preservative. The sugar, called trehalose, is produced by organisms living in some of Earth’s most extreme environments as a way to survive long periods of drought. It is relatively cheap and is used as a food preservative.

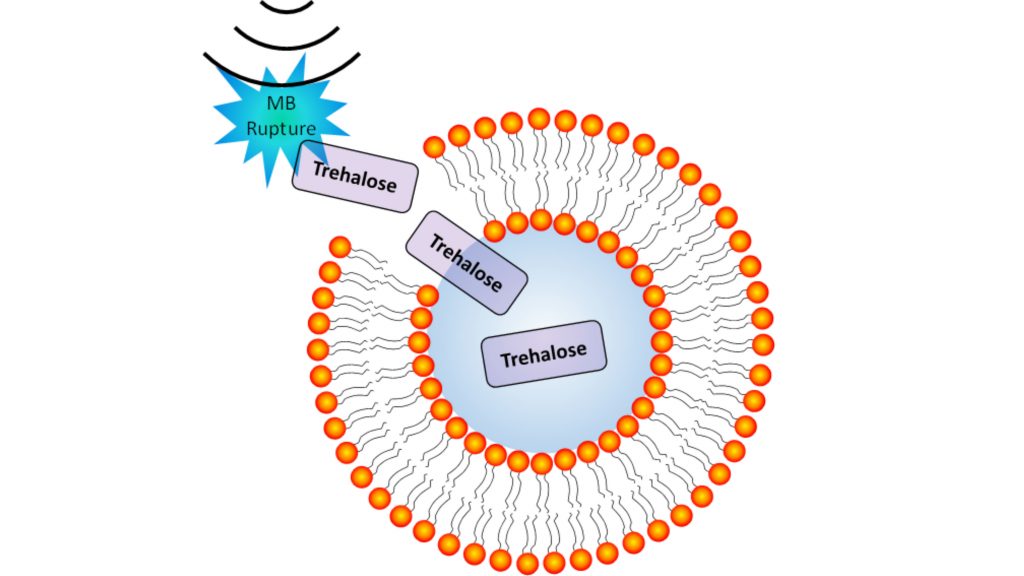

Researchers at the University of Louisville have developed a method to insert trehalose into red blood cells using ultrasound technology. The ultrasound creates what is known as a microbubble (MB) rupture, forming a temporary pore in the cell through which soluble materials like trehalose can enter. This sugar helps the cells prevent degradation when they are dried. Oscillating gases around the cells with the use of ultrasound tech also increases the number of viable cells that are able to be re-hydrated.

It is estimated that this method (which does not require freezing or refrigeration) could increase the shelf life of whole blood from weeks to several years. This would not only help with the global need for blood supplies, but also be especially important for people in situations where access to donations is difficult, such as on the battlefield or in space. The researchers from this project are currently hoping to perform more tests focusing on increasing the yield of viable blood cells from the re-hydration process.

Original story and interview by Larry Frum.

[Note from the author: I’d like to apologize from my extended break from stories on the site. Transitioning work environments due to the virus took a greater toll on me than I had expected, and I’m sure others have experienced similar circumstances. I plan to continue writing for the site, hopefully with variety and not all COVID-19-focused!]

References

- Centner CS, Murphy EM, Priddy MC, Moore JT, Janis BR, Menze MA, DeFilippis AP, Kopechek JA. 2020. Ultrasound-induced molecular delivery to erythrocytes using a microfluidic system. AIP Biomicrofluidics 14.

- Frum L. 2020. Ultrasound-Assisted Molecule Delivery Looks to Preserve Blood for Years. AIP Publishing. AIP Publishing.

- Sarkar S. 2008. Artificial blood. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine 12:140–144.

- ASH. Blood Basics. Hematologyorg. American Society of Hematology.

- Korcok M. 2002. Blood donations dwindle in US after post-Sept. 11 wastage publicized. Canadian Medical Association Journal 167:907.